The ‘Constitutional Fix’ That Could Erase Our Haitian Citizenship

As Haiti approaches the February 7 deadline, one proposal has regained momentum among political actors in Haiti and abroad: a judge from the Court of Cassation, the country’s highest court, should assume the presidency to help resolve the current crisis. Supporters argue that a judge could stand above the political factions and, since most institutions have collapsed, offer the last viable path back to constitutional order.

I wrote an op-ed on this issue almost two years ago, titled “Haiti’s Crisis: A Political Problem with No Judicial Solution.” I argued then that “while appointing a Supreme Court justice as Provisional President might seem like a straightforward solution to Haiti’s complex issues, it is a deeply flawed approach that violates the integrity of the Constitution and risks dragging the court into a political crisis it cannot solve.”

Two years later, I do not doubt that some proponents of this proposal are acting in good faith, but many are not. Still, I do not dismiss the idea of a judge from the court as a possible political option. What I challenge is the effort to cast this choice as constitutional rather than political.

To support their case, proponents of the Cassation option cite the interim presidency of Ertha Pascal-Trouillot following Prosper Avril's resignation as a precedent. But 2026 is not 1990, and the context is different. Others argue that this approach honors the “spirit” of the non-amended 1987 Constitution. This argument requires us to ignore the current Constitution, which the justices in the court have sworn to protect and have applied for more than fourteen years.

It is difficult for me to say this, but in a country where no institution is seen as legitimate or trustworthy enough to mediate among political actors, I have avoided participating in this debate for three main reasons.

First, I believe Haitians will not reach a lasting political agreement without the intervention of the “international community.” Second, I see the current crisis as primarily political rather than constitutional. Third, I strongly believe that resolving it does not require dismantling the amended Constitution, as doing so could threaten the rule of law and cause more harm than the crisis itself.

Ultimately, my main concern is the potential impact of this decision on millions of Haitians whose rights are protected by the constitutional system governing them.

A Disagreement Rooted in Principles

The entry point of any debate about Haiti has to start with a clear eye view of the country’s social and political class. Haitian elites thrive on chaos and seldom reach consensus. When they do, it is often not worth the paper it is written on. As a result, most crises require the international community's intervention, and this one will be no exception.

I understand the instinct behind picking a judge from the Court of Cassation. Since the country’s institutions have collapsed, people are reaching for something that feels solid and legitimate. A judge carries symbolic weight and may appear less political. This is an argument that can be made straightforwardly and earnestly. However, presenting it as a constitutional choice rather than a political one is where the reasoning breaks down.

Every policy choice carries risk. One lesson from the Transitional Presidential Council (CPT) is clear: its lack of legitimacy left it weak and easily influenced. If a judge is to succeed the CPT, they would need broad support across institutions and civil society. Installing a judge without consensus would place them in an even more fragile position than the CPT, forcing them to contend with both political and economic pressures at once with a weak hand.

Another concern is the assumption that a small group of political actors can erase a constitution that was amended through proper procedures and has governed the country for more than fourteen years. Haiti’s courts have operated under that framework, under which rights have been recognized and enforced.

This choice would require the judges who swore an oath to uphold the 1987 amended constitution, and who have applied it for over a decade, to now reject that oath.

Supporters of a judge-led transition counter with several arguments. Some point to procedural flaws in the 2012 amendments, including the failure to publish the text in Kreyòl. Others argue that when Parliament ceased to function, the amended constitution’s line of succession became unworkable, requiring a return to the “spirit” of the original 1987 constitution. Still others invoke precedent, citing 1990 under Ertha Pascal-Trouillot and 2004 as moments when a judicial figure helped bridge a political rupture.

These arguments deserve consideration, but they share two fundamental weaknesses: timing and practice. The failure to publish the amendments in Kreyòl is a legitimate concern. Yet in practice, Haiti’s administrative and judicial systems have long operated primarily in French. Courts, attorneys, and public officials applied the amended framework for fourteen years without objection. Raising this issue now to invalidate more than a decade of jurisprudence is not persuasive.

Indeed, discarding fourteen years of legal practice because it is inconvenient is not a return to order. It is a sure way to deepen the chaos and destroy the judiciary.

The Citizenship Question

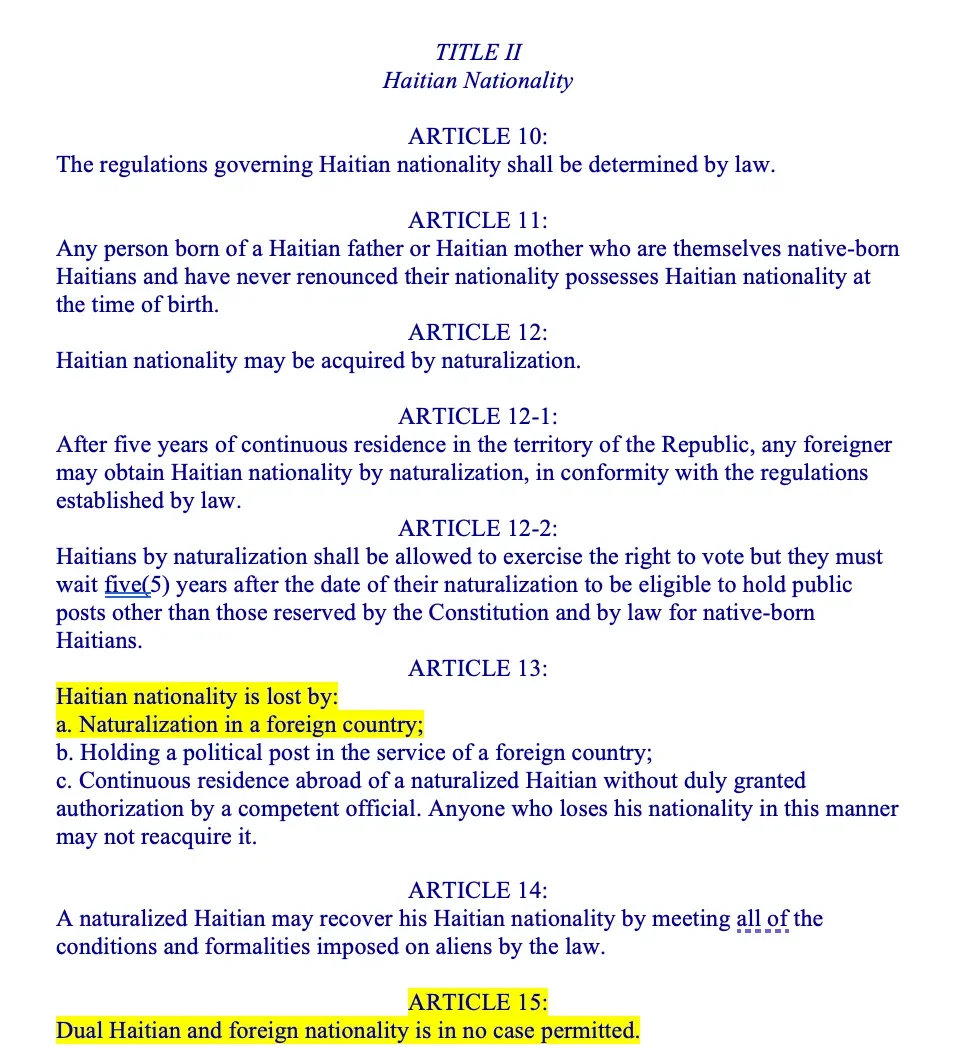

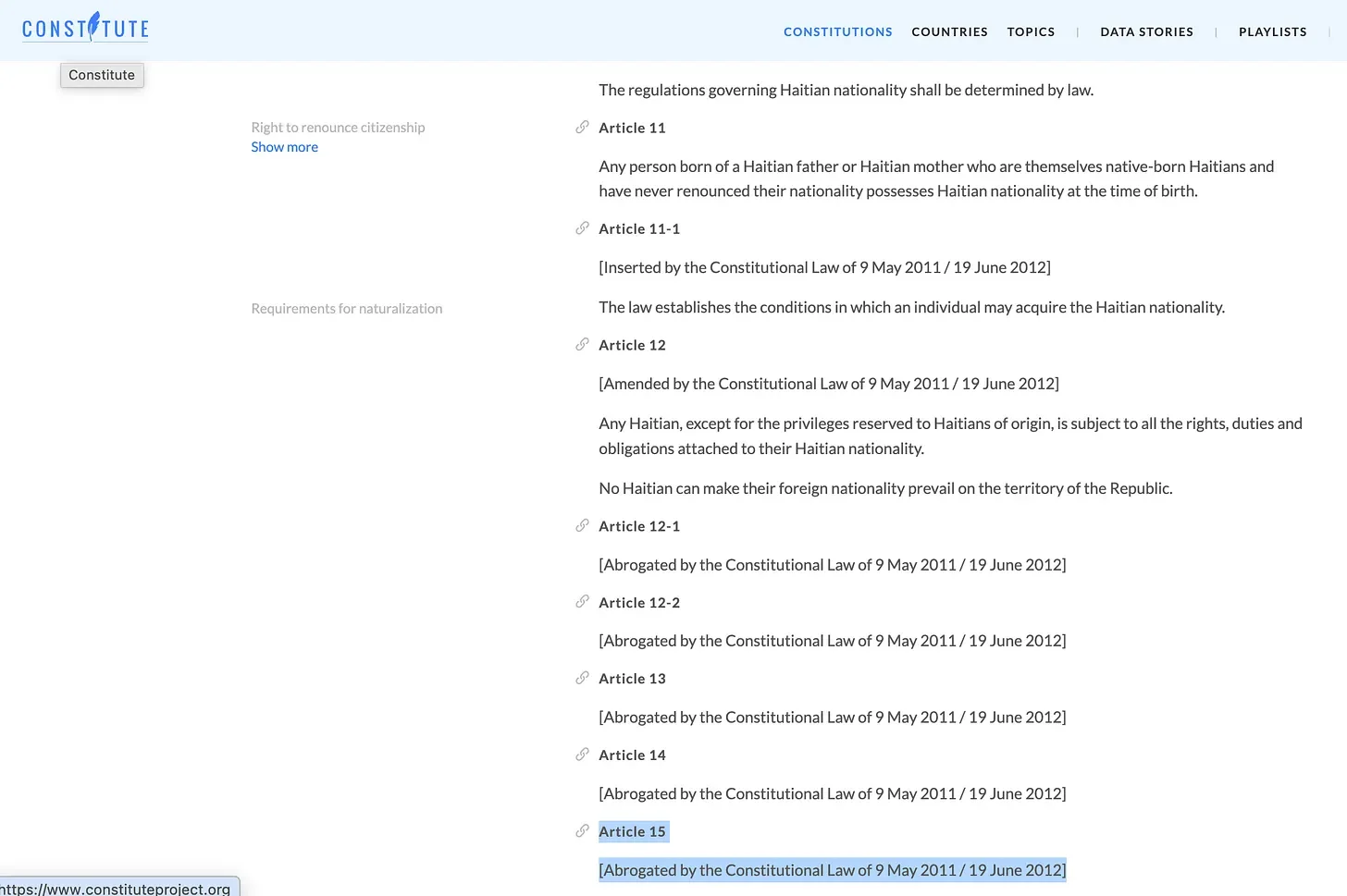

The most serious consequence of reverting to the original 1987 Constitution is its impact on citizenship. Before the 2012 amendments, the Constitution prohibited dual nationality. Article 15 was unambiguous: “Dual Haitian and foreign nationality is in no case permitted.” Haitians who became citizens of another country automatically lost their Haitian citizenship. The amendments removed that prohibition, allowing Haitians like me, who live abroad, to hold dual nationality.

Citizenship is fundamental to identity and legal rights. Removing it arbitrarily is not a constitutional adjustment but a cynical or, at best, a thoughtless attempt to exclude Haitians abroad. As a Haitian American, I am not willing to give up that right.

When Law Becomes a Tool for Power

We should be clear about what is happening. This is about power. Yet what is most striking is that even among those who support selecting a judge, there is no shared understanding of how to do it. There is no agreement on which judge should lead the transition or on the principle to follow.

One group supports the court’s president. Another backs the longest-serving judge. Yet another proposes a lottery system where they would pick one of three. There is no consensus among supporters of the court option on how to fill the gap, except that they want their own judge.

This fragmentation reflects a debate that has drifted away from constitutional order and toward power. Competing factions are advancing their preferred outcome; each wrapped under the guise of legality. When the law is applied selectively to justify political preferences, it loses its authority. What remains is not constitutional order, but competition over who can impose their chosen outcome while claiming legitimacy.

Cassation Is a Political Choice, not a Constitutional One

A judge from the Court of Cassation may still emerge as a political compromise, but it should not be presented as a constitutional one.

Haiti has been governed by the amended constitution for fourteen years. This framework has shaped legal decisions and protected certain rights. Declaring it invalid because it no longer benefits some actors is a political move, not a legal one. Those who believe a judge is best positioned to lead this transition should make that case openly. They can argue that institutional collapse leaves no better alternative and acknowledge the risks. That is a political argument, and it deserves serious debate.

I believe the proponents of cassation can and should make a straightforward political argument for their choice. However, framing this political decision as an effort to honor the “spirit” of a Constitution that was amended and in force for fourteen years is to try to sell us zanana pou sizàn. Haiti faces a fragile and perilous moment, and we must clearly understand what we stand to gain and what we stand to lose with these choices. Failing to do so will deepen the crisis rather than resolve it.

What unfolds next will shape the nation’s direction for many years; therefore, we must insist on clarity, accountability, and respect for the millions whose rights are at stake. The proponents of the Court of Cassation option must sell it to us by outlining its benefits and risks.